Anna Post

(alias: Salome Czaplinska)

Born in 1923 in Bronocice, Poland. In 1961 her family immigrate to the United States. Anna became a teacher at Kadimah Academy in Buffalo, New York, where she taught for over 30 years.

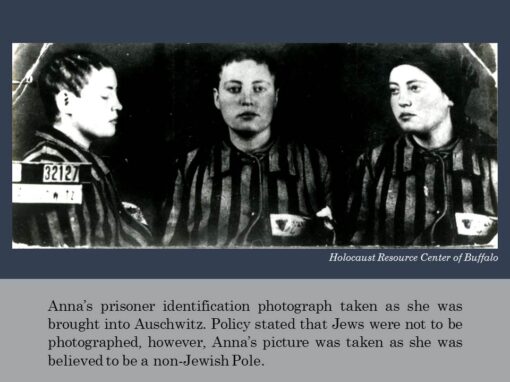

Anna Post’s Biography

Anna [Dula] Post was born in the small village of Bronocice, Poland in 1923 to Leibish and Rivka Dula. She was the youngest of six siblings, three boys and three girls and was raised in a very religious household. The Dula Family ran the local flour mill and were the only Jewish family living in the area.

In 1929, the Dula family moved to the small city of Dzialosyce, which had a strong Jewish contingent among its almost 7000 people. This was the main motive for the move from the isolation of the countryside, but it was also so that the children could further their education, as schooling didn’t go beyond elementary school in the countryside. After some adjustment, by and large Anna had a happy childhood. By the summer of 1939, when Anna was 16 years old, she recalls the Polish radio in July and August brushing off any concerns about the Nazis; then suddenly her city of Dzialosyce was among those occupied by the Nazis on September 1, 1939.

The Nazis soon established their anti-Jewish laws inside all their captured dominions. Dzialosyce was soon flooded with refugees from larger towns who were fleeing the ghettos, resulting in 20 people living in her house. By 1941, all Jews were required to register their identities with the government. They had to wear the armbands with the yellow Judenstern — the six pointed star — whenever they went out in public. Also, all Jewish businesses were being “Aryanized” confiscated and turned over to non-Jewish owners. Anna’s father spent ten weeks showing the operations of his business to a German manager, and then was kicked out without any compensation. Jewish families had also been relieved of their homes, and placed into small apartments in a designated area. These apartments had two rooms: A kitchen, and a living/sleeping area. In these small spaces dwelt as many as ten or fifteen people. And there was as little freedom outside. The Nazi curfew meant everyone had to be back inside their homes by 6 pm.

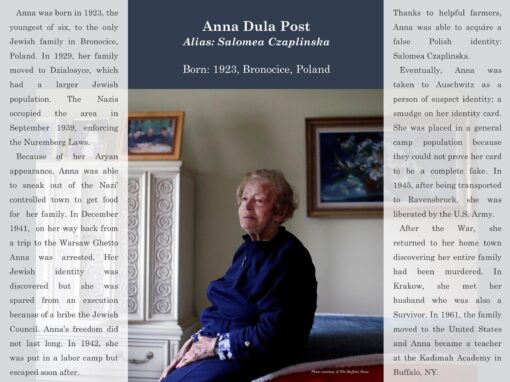

The Germans were also interested in breaking the Jewish spirit. Jewish services and the teaching of the Jewish faith were outlawed. There was to be no education of any sort for Jewish children. Many Polish Jews felt that the Nazi oppression couldn’t last, and so continued to secretly prepare their children for resuming their studies once the War was over. Illegal “schools” were set up in basements and other clandestine places. Anna’s sister taught dozens of children in one of these classrooms in their home.

As a further embarrassment, Jewish men were required by law to shave off their beards. Some, like Anna’s father, viewed the beard as part of their faith and heritage, and refused. Eventually he was taken on the street by Nazis and forcibly shaved. Anna recalls that he was never the same man again after this humiliation. Since Anna was blond haired and blue eyed, she was confident about her ability to blend in. She began making trips for the family by not wearing her armband, and sneaking out to a nearby city where she was not known and trading linens and other items for food. In September a man who had escaped the Warsaw Ghetto came to Dzylosice. He told people of the horrendous conditions and widespread starvation there. The Dula family had some cousins who lived in Warsaw. They resolved to try to help them any way they could. Anna took the train up to Warsaw, carrying a slab of lard to give to her relatives. She was able to enter the ghetto under the pretense of being a gentile woman who wished to sell the lard to the Jews. The ruse worked, and the food was delivered. Anna made several such trips to Warsaw over the next three months.

On returning from Warsaw for the final time around Hannukah, in December 1941, Anna was changing trains in Miechow, as usual, when an SS man pulled her aside. Her fear betrayed her, and Anna was discovered. She was taken to the Gestapo headquarters and told she would be summarily executed for the crime of impersonating a non-Jew. She was given a shovel and taken out back to dig her own grave; but Anna was small and took too long digging; her execution had to be put off until morning.

When the morning came, the SS man came to Anna and told her her life was to be spared. He offered no explanation for this decision. She was put on the next train home. It was only later that Anna discovered what had happened. It seems the Miechow Jewish Council had gotten news of her plight, and had bribed the Germans to let her go. So it was in those days, that concern and aid could be extended even to a total stranger, and even during troubled times.

In 1942 there were massive deportations. Entire cities were cleaned out. The ablebodied who remained were sent from the city to the countryside on forced labor crews. Anna went out daily on one such work detail. One day, she was warned by some girls not to return to Dzylosice that evening with her work detail; that day, the remaining Jewish population of the city had been either killed or removed by the Nazis. Anna took their warning to heart and, near dark, she separated from her work detail and began walking down a dark, lonely road. After a while she encountered some young men, local farmhands, who offered to help her get away. The gave her some clean clothes and got her to the city of Wislica, where there was still a Jewish population left. She stayed with some former neighbors who had known her family from years past.

Thanks to the farmhands, Anna was able to acquire some false papers bearing a non-Jewish identity. The forged birth certificate and identity card bore the name of Salomea Czaplinska. They were excellent forgeries, but ink got smudged on the ID card while Anna was adding her fingerprint, making the ID questionable.

Later, Anna found two of her brothers were living in hiding in a bunker beneath the apartment of a sympathetic Polish widow. There was no more room in the bunker, so it was arranged for Anna to hide in the attic of a farmer who lived on the outskirts of town. Anna lived there for a few months, but there was nothing for her to do but hide. She tried to keep her mind occupied, but it was no use; if she remained there, she knew she would go crazy. She ended up leaving the relative safety of the farm.

Anna went to the city of Krakow and found a little work in shops and factories. She ate her meals in various soup kitchens. She was totally alone, knowing no one in Krakow. She knew that it was up to her to either survive on her own, or perish. One day the SS closed off the street and began checking IDs. Anna knew there was no escape, and she doubted that her false ID would pass inspection. She decided to destroy it and take her chances as an unknown person. She was arrested for failing to carry Identification.

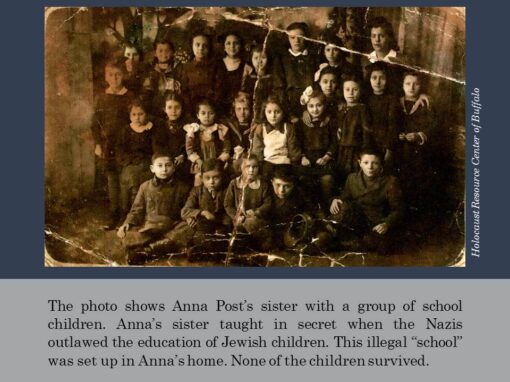

Anna was sent to Auschwitz as a person of suspect identity – but she was never identified as Jewish. Instead of being routed directly to the crematorium, Anna was placed with the general camp population and assigned to forced labor. She remembers her arrival through the gates of Auschwitz well. She was lined up and marched into a huge hall where her clothes and possessions were taken from her. Then she was shaved of all body hair, sheared like a sheep. Then she got her tattoo. From then on she was known as number 32127. She was photographed and made to feel like a criminal. By taking away one’s name and identity, the Nazis broke people down so they would lose the will to fight back, even to live at all. Anna caught sight of herself shaved and in her camp uniform and with horror found she no longer recognized herself. Jews were not photographed as a matter of policy, to aid and abet the “Final Solution”. Anna was photographed because she maintained the pretense of a non-Jewish identity.

In Auschwitz, they slept ten to a bunk, which was nothing more than a wooden platform, with no mattress or pillows. They had one thin blanket to spread between them, so no one slept very well. In the morning there was a roll call. There were weekly “selections”, to pick out those no longer healthy enough to work. If you looked bad, you were told to go into a line to the left. Those in that line were always taken to the crematorium to be killed. Anna, like many others, got sick with typhoid. She and some friends did their best to conceal her sickness during selections, even when she was running a high fever of 105 or 106 degrees.

Near the end of 1944, the Russians were closing in. The Red Army was just across the river Vistula from Warsaw. The Germans made plans to pull back with their remaining prisoners. On January 16, 1945, the prisoners were assembled, and they marched out of Auschwitz, moving west. They were taken on a Death March. Every few minutes, someone would collapse into the snow and they would be shot by the Germans. They marched from first to last light for six long days in the dead of winter. They came to a spot where they were loaded on a cattle train. The cars were open at the roof, and so some snow got in for the “cargo” to get water from. Snow was all they had to eat during the five day journey to their destination.

The prisoners were taken to the Ravensbruck camp, where they were housed in tents that were open to the elements. Each tent was packed wall to wall with people. Another week passed. Then Anna and some other prisoners were taken to the Neustadt-Glewe subcamp in Northern Germany. They were put to work painting planes for the German Air Force. They were supplied with no food. All they could scavenge was some dead grass and tree bark. While chewing these, some people talked of baking cakes. All Anna could dream about was a loaf of bread for herself, and a clean, quiet room to eat it in. Everyone was nearly mad with hunger.

Winter became Spring. The Allies continued to advance. One day in May, there came a sudden quiet. There was no more shooting, no more screaming. The prisoners looked around. The Germans had gone. Then came the sound of jeeps approaching. The U.S. Army came, saying the Germans were on the run. The soldiers that came looked to them like angels and supermen. The former prisoners had to touch them to make sure they were real, and they embraced them and kissed their uniforms. Nearby was a grassy hill with trees and flowers, and they danced around the trees and kissed the grass. They felt the miracle of freedom, and the promise of a new beginning. The soldiers gave out food to everyone, including chocolate and sardines. Many survivors got sick from this because their bodies were so unused to digesting real food.

After some recovery time, Anna went back to Poland, to search for any relative who might also have survived. She came back to Dzylosice, where she had grown up. She went to her old apartment, and was told by the landlady that her parents had been taken away. Anna later found that her entire family had been murdered in the Nazi camps. Some Poles still carried a hatred of Jews, and searched the city by night for any returning refugees. Those they found they killed. It wasn’t a safe place for Anna to be. In time Anna met other survivors but they were too grief-stricken to celebrate their freedom. No one knew where to go, what to do. Mostly they had no family, money or homes left. Nobody was there to welcome or to take care of them. It was a struggle to re-enter normal life. In time they slowly formed friendships among the other survivors which gave them the moral support to go on. They had cheated death, and they weren’t about to give Hitler a posthumous victory.

She came to live once more in Krakow, where she met a man who became her husband. He was also a Survivor, a former prisoner of the Mauthausen camp. Anna went back to school to finish her diploma. She became interested in pursuing a career in medicine. Anna had a child, a boy, in January of 1948, which helped Anna regain a love of life. In 1953 her daughter was born, and the joy of having a family was complete. These children were her only blood relatives now. Poland was under a Communist regime, which was very oppressive. In 1961 the family emigrated to the United States. Anna became a teacher at Kadimah Academy in Buffalo, New York, where she taught for over 30 years.

CLICK ON THE IMAGES BELOW TO LEARN MORE ABOUT ANNA’S STORY

Anna Post’s video interview with HRC Founder Toby Ticktin-Back

CLICK HERE TO REQUEST A SPEAKER

Our speakers can present in person or online.

Our speakers are all volunteers. An honorarium to HERO is greatly appreciated. We are a non-profit organization and honorariums make a significant difference in our ability to continue our impactful work.

"*" indicates required fields